Back from Afghanistan

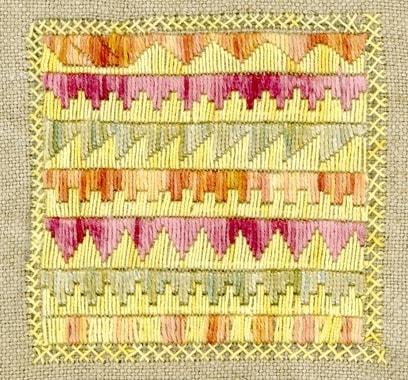

Embroidery project in Laghmani

May 2006

Let us begin with the “and more” – the struma patients

I noticed the year before that many people there suffer from an enlargement of the thyroid gland. It’s mainly women who are affected, but also children. Hyperthyroidism is widespread in Afghanistan – a country of mountains – and is attributed to iodine deficiency. As a great number of our embroiderers were affected, so I asked Anne Hermes, a nurse and also a member of the DAI e.V., who had already worked on projects in Afghanistan twice before, to accompany me.

The embroidery project: We meet embroiderers again, become acquainted with interested women and make contracts

In Kala-i-kona, Sufian and Kakara we – Weeda, the interpreter and I – had contact with some 300 women. I was overwhelmed by this response; until then up only 80 women had officially taken part in our project. Among them were women who officially embroidered, meaning that I knew them from the previous year, or to whom Weeda distributed embroidery cottons and from whom she had bought embroidered squares. But among the 300 were also women who claimed that they could embroider and who wanted to be included in the project.

Moreover, I had decided to pay the women by a different method; up to then, they had been paid when they delivered their squares. For organizational reasons, the women will now be paid for their last batch when they deliver the next one

I have made contracts with a great number of unmarried girls between the ages of 12 and 20 although their embroidery is not yet up to standard. This is in part my own ‘policy’. By supporting the girls financially I want to give this traditional technique a chance to prevent it from getting lost in the future. It is my personal, deliberate and perhaps naive attempt to revive these dying techniques.

The payment before my departure

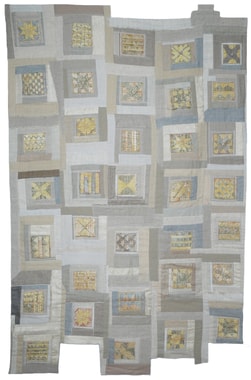

I had chosen the two days preceding my departure to handle the payment in the 3 locations of Laghmani in order to give the women as much time as possible to complete their embroidery. All the women could sell their embroidered squares to me, including women with whom I hadn’t an agreement. More than 6000 squares were collected making it the last time for so many squares to be gathered!

What I might do differently another time and ideas for the future

The difficulty of deciding who is good enough at embroidering, i.e. with whom can I make a contract is very difficult and sometimes seemed unjust, because some “new” women haven’t embroidered in 20 years and simply need time to practice. In the future, I would like to provide the women with information about the new acceptance procedure. Two months advance notice would give them a chance for warming-up.

Miscellaneous

Women apparently love this unexpected way to earn money (I could have made contracts with more than 300 women). It is a completely new experience for those who have never had a chance to earn money. Apart from this – and by asking around – it proves to be true that women enjoy embroidering very much. We should however not judge this activity as a hobby in the European way.

My misgivings that men would snatch the money and use it unlawfully proved untrue. The women themselves decide how to spend it. According to tradition they give money to the men as they themselves can’t shop. The money is normally spent on food, firewood, gas cylinders… Unfortunately none of the women have invested in something bigger such as a calf; maybe because there wasn’t enough money or because food had to be bought for the winter. Doctor’s fees were also paid. The unmarried girls can keep their money some of which was invested in clothing (denim jackets!).

General impressions

Again I was very happy to be the guest of a typical and traditional family. This year, the tshadri (burka) which last year hung on a nail next to the entrance had disappeared. During my stay, I witnessed the day when the 20-year old daughter went to school for the first time in her life. What a huge success after many years of suppression and moving around! Finally she found her peace of mind and with it the desire to go to school. She asked her father for permission.

Kabul remains extremely dirty and dusty. Even if a few streets have been asphalted, a few minutes of rain turns it into mud. It’s difficult to say which is worse! Nothing much has changed for the population; the wages are still so disgracefully low that nobody can live on them. Several jobs are needed in order to survive including thieving. Women can only find work as teachers or nurses.

I left Afghanistan from a small, dirty airport with final glimpses of soil and dust, occasionally interrupted by green valleys winding like snakes into the mountains. Then came the “white-out” provided by thick layers of clouds. After a couple of hours the sky opens above green forest and accurately laid-out fields. The plane lands in Frankfurt, its airport gigantic, clean and cool in marble.

People are people, be it in Afghanistan or Germany; otherwise, I could have thought I had landed on a different planet or in another age.

Pascale Goldenberg